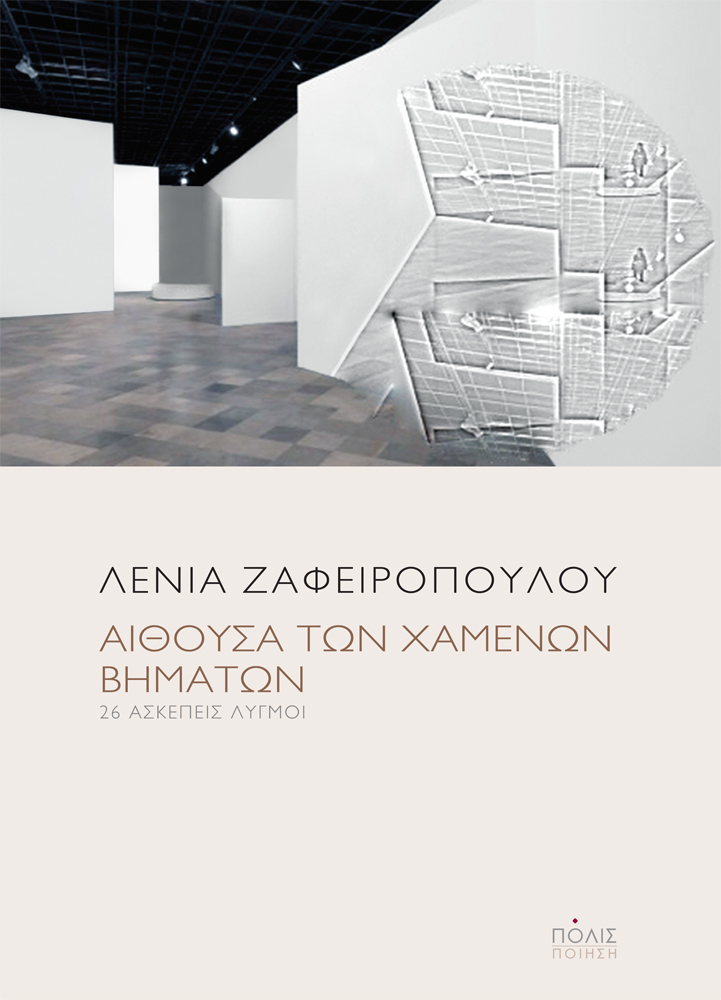

Lenia Safiropoulou is an opera singer, poet and translator. She has published three poetry books: Paternoster Square (Polis, Athens 2012, Prize of the journal “Anagnostis” for young authors), It is hard to stumble on stones (Patakis, Athens 2016, Prize “Woman of the Year” 2017) and Hall of the lost steps (Polis, Athens 2019, winner of the A.C. Laskaridis Foundation poetry competition). Her poems have been translated into English and German. She has translated into Greek poems by Goethe and Heine, as well as the complete sonnets of William Shakespeare and Tsar Saltan by A.Pushkin.

She has studied singing, piano and art song in The Musikhochschule in Stuttgart with scholarships of the Maria Callas and Alexandros Onassis Foundations, and opera at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and the National Opera Studio in London, supported by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. She has given recitals in Athens, London, Paris, Lyon, Berlin, Hamburg, Barcelona and Nicosia and has sung with British and Greek symphony orchestras, and participated in productions of Greek National Opera and the Athens Festival. In 2017, her personal album Sunless Loves, with works by Brahms, Prokofiev and Mussorgsky, was published by the British label First Hand Records. She is a producer of the National Greek Cultural Radio ERT3.

Lenia Safiropoulou spoke to Reading Greece* about her latest writing venture Hall of the lost steps, built around the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, which gave her the opportunity to imagine “how he might be an intimate, last hero in a centuries-long line of heroes”, adding that “what power institutions aggrandize through literal discourse, art may undermine through the use of irony”. She considers that “poetry, the theatre and music are indeed communicating vessels”, and comments that “poetry and music share the same rhythm, abstract language and leaps in thought”, both aspiring to “create an autonomous world that operated beyond, or even against, the rules of literal sense”.

Your latest writing venture Hall of the lost steps (Αίθουσα των Χαμένων Βημάτων) received quite favourable reviews and was characterizes as a work of maturity. Tell us a few things about the book.

Hall of the lost steps is built around the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, whose work and fate unexpectedly, and somehow imperceptibly, became for me the focus of poetic reflection. Mandelstam was vehemently prosecuted by the Soviet state and died prematurely in exile while his work was salvaged by his friends in a way nothing short of miraculous. He occupies in the public mind the place of one of the last heroes and his story is one of the last myths. In my previous books, too, I concentrated on power and its multiple facets in our life. Mandelstam became for me a kind of “embodiment”, an incarnation of my theme. He offered me the opportunity to imagine how he might be an intimate, last hero in a centuries-long line of heroes. There are only few poems in the book that directly refer to Mandelstam. Nevertheless, as I was thinking of him, trying to invent him in words, I realized that such a last hero would wear a kind of fancy costume, with multicoloured patches of both heroism and anti-heroism. And this feeling led me to other poems centered on my own life and position in the world. As Heinrich Böll put it in an interview, maybe the only way to mold a hero nowadays is to mold your own “Christ figure”. Böll himself, uses to that end such models as the Idiot of Dostoyevsky and the Stranger of Camus. I, in turn may have as my model Böll’s Clown. In my book, Mandelstam, Orpheus, Prometheus, Lazarus and a self-derisive poetic persona, constitute different roles of the same person. What power institutions aggrandize through literal discourse, this peculiar last hero, Mandelstam, undermines through the use of irony.

In your poetry, you seem to borrow themes from political and art history in order to delve into questions of power, individualism and social exclusion in the west. Tell us a few things about the main issues your poetry touches upon?

The Western world has for centuries operated on expansionist and imperialistic premises. It has also operated through selection and exclusion. It has operated as a Castle, as described by Kafka in his book of that title. You don’t need to be a refugee or a worker from a poor country to understand that. If you are young, i.e. at a stage when your position in the world is still uncertain, and live in a major economic or cultural European center, you see yourself surrounded by smaller or larger fortresses that challenge you and at the same time impede you from conquering them. We are a world of above and below: we perceive life as an escalation upwards: towards constant development and self-realization, towards happiness, acclaim and influence. As you know, this is the way for castles to be conquered, by climbing rope ladders.

References to history and the history of civilization are for me a kind of cloakroom, a bag full of theatrical props. Yet, it’s also a state I induce in myself in order to write. If you want to address some of the blights of your culture and aspire to produce a work of art, rather than an academic essay, an opportune way is to efface your ego, with its restricted age and its restricted present. Then, you may be able to see yourself reflected in quite remote and foreign forms. That is how you gain access to the variegation and the transformation potential which art requires.

A mezzo-soprano, a poet and a translator. What is that binds all these different attributes together?

Although I am a professional musician, my relationship with art didn’t start with music. It started with a passion for books and the theater. A passion for literature, that is for narratives and a passion for the theater, i.e. an escape from myself, led me to the opera and singing. It was in late adolescence, that I fell in love with Lied, i.e. poetry set to classical music. Thus, when around the age of 30, I felt capable of writing for the public, it was poetry that automatically came out. Probably because poetry and music share the same rhythm, abstract language and leaps in thought. Also because poetry, like music, aspires to create an autonomous world that operates beyond, or even against, the rules of literal sense.

To use Ezra Pound’s words, “poets who are not interested in music are, or become, bad poets”. Would you characterize poetry and music as communicating vessels?

For me poetry, the theater and music are indeed communicating vessels. Yet, the history of art has proven that there is an infinity of ways to create good art and they are often contradictory. There have been innumerable movements that were created in order to undermine and overcome the ones preceding them. Art is born not only by following existing paths but also by ignoring them and paving instead a path through the wilderness. Undeniably, familiarity with more than one art form offers an overview of your culture and connects you with artists before you. It lifts you, so to speak, up on a hill, offering an unobstructed view. Nevertheless, in the history of art, someone always appears who performs miracles, without meeting any of the prerequisites. Which is why there is no room in art for dogma.

How would you comment on literary and artistic production in the era of online communication? How do literature and music relate to modern reality?

The internet has inundated our life with the written word. Everybody reads and writes, nowadays, even people who previously didn’t use to read or write on a daily basis. We have a massive quantity of written text at our disposal at any given time. All those involved in artistic discourse, are called on – today more than ever – to conscientiously sift through our writing. Many of the tasks that used to be assigned to art are nowadays taken up by the innumerable texts on the Internet: confessions, auto-fiction, social and political commentary, testimonies and research studies of every sort. Yet, art still has plenty of other tasks to carry out: the fusion of feeling and reasoning, of ascertainment and intuition; the distillation and elaboration that are so sorely lacking from our exponential world; the persistence and dedication so little in evidence in internet surfing and digressing; the expansion of the present, the escape from our ego, the questioning of appearances. Mounting a defense against the virtual reality trying to convince us that we are no more than our ego, our present moment and our imprint.

In recent years, there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares to mention just a few. How would you comment on this strong civic awareness?

Poetry in Greece is, I believe, looking for ways to access a stronger and more public voice. It’s a move in the right direction given that the Internet has turned our entire written discourse public and accessible. Out of all the voices, why should only that of poetry remain private and personal? Still, let poetry continue to write texts that require concentration, silence and multiple readings. To ask from poetry to operate in fast-forward mode, in noisy city squares and hurried presentations, would be to take the wind out of its sails and blunt its sting. Even worse, it would dangerously curtail the artist’s freedom to pave the way into uncharted territories, and then invite those who have the inclination, courage and time to follow.

How do Greek writers relate to world literature nowadays? How does the local/national interweave with the global?

Due to globalization, art movements and trends have become more publicly accessible than ever. In Greece, as everywhere, you can find a love for what is native and a new ethnography. Here, as everywhere, the influence is discernible of anthropology and reportage: personal and authentic testimonies, the interweaving of political history with autobiography. There is an emphasis on gender identity and a demand for social integration, alongside a concern for worldwide problems of social inclusion, poverty, migration, ecological disaster, social inequalities. At the same time, you can find personal pantheons as a starting point for personal mythologies, as I try to do with Mandelstam in Hall of the lost steps. We live in the era of the individual in its ultimate form: everybody has their personal gods, their own eclectic mix of ideas, tastes and habits. Because, however, art has never moved forward solely through co-existence but through reaction as well, the chaos and terra nullius of globalization prompt today a neo-romantic tendency towards the familiar, the local, the authentic and the primordial.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

*INTRO IMAGE: @Nikos Koustenis

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE