November 17 commemorates the Athens Polytechnic Uprising in 1973, which was a massive demonstration of popular rejection of the Greek military junta of 1967–1974. The uprising actually began on November 14, 1973, and escalated to an open anti-junta revolt and ended in bloodshed in the early morning of November 17, after a series of events starting with a tank crashing through the gates of the Polytechnic.

The poetry collection titled The Body and the Blood (One more attempt at a poem for the Polytechnic) by Yannis Ritsos refers to the Polytechnic uprising, to the limitation of the body that acts and claims the “unfamiliar” within space, to the intervention of an extensional ‘youth’ that becomes ‘body and blood’. The moment the body stands against the tank, freedom is ‘re-invented’. Yet, there is no heroic action except an openness to death, the shaping of the conditions for the incarnation of the ‘generous’ action. In this framework freedom is constituted in action, in uncertainty, in the scope of reaction, the potential and the non-death.

II

[Excerpts from The Body and the Blood (One more attempt at a poem for the Polytechnic) by Yiannis Ritsos, translated by C. Capri-Karka and Ilona Karka]

The poet

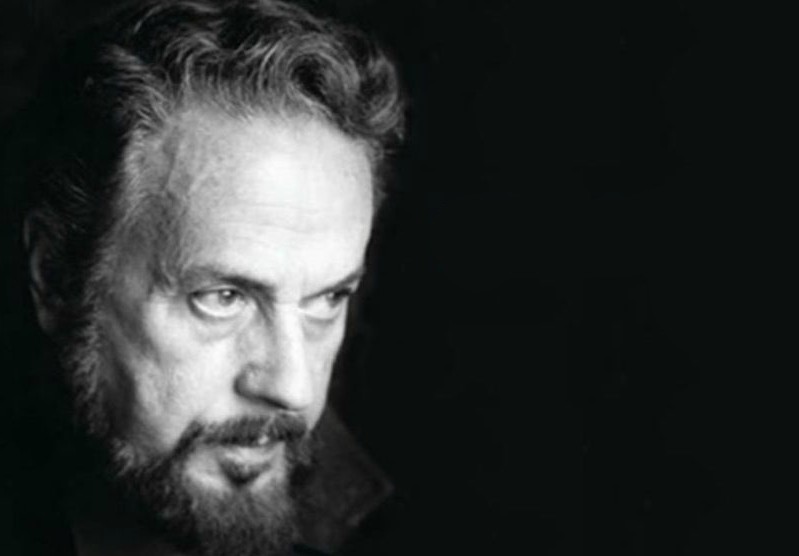

When Yannis Ritsos passed away on November 11, 1990, the world of poetry lost one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. “Yannis Ritsos,” wrote Peter Levi in the Times Literary Supplement of the late Greek poet, “is the old-fashioned kind of great poet. His output has been enormous, his life heroic and eventful, his voice is an embodiment of national courage, his mind is tirelessly active“.

Plagued by turberculosis, family misfortunes, and repeated persecution for his Communist views, he spent many years in sanatorums, prisons, or in political exile while producing more than 100 poetry collections, 9 novels, and 4 theatrical plays. Epitaphios, Romiosini and Moonlight Sonata are three of his best-known works. In 1975 he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. When he won the Lenin Peace Prize in 1975, he was quoted as saying that “this prize is more important for me than the Nobel”. He also wrote countless articles and made numerous translations of other works.

Ritsos’ poetry ranges from the overtly political to the deeply personal, and it often utilizes characters from ancient Greek myths. At their best, Ritsos’ poems, “in their directness and with their sense of anguish, are moving, and testify to the courage of at least one human soul in conditions which few of us have faced or would have triumphed over had we faced them“, as Philip Sherrard noted in the Washington Post Book World. In long poems like his celebrated Romiosini (1947), Moonlight Sonata (1956) and most of his later volumes, Ritsos writes with compassion and hope, celebrating the life, toil, and dignity of the common man in an unadorned and direct language.

To use Pantelis Prevelakis’ words, “Without Ritsos’ eloquence, Greeks would have forgotten how to name a major part of all those things that are there before their eyes. […] Sometimes like an all-seeing sun, sometimes like a lantern-bearing thief in the night, but never devout, never a naturalist, Ritsos verily surveyed Greek space and delved deep in many of its folds”.

A.R.

Read also: Greek News Agenda: Athens Polytechnic Uprising 47th anniversary

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE