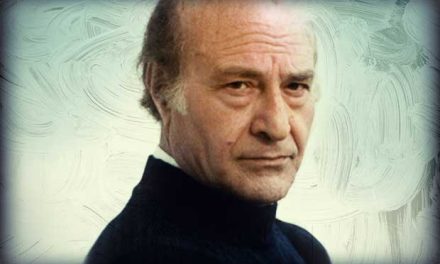

Christos Siorikis (1989) grew up in Agrinio and lives in Athens. He works as a Spanish teacher and translator. His poetry collection The First Time (Antipodes, 2018) was nominated for the Anagnostis literary magazine award for best poetry debut. He has translated works by Julio Cortázar, Eduardo Galeano, and María Zambrano.

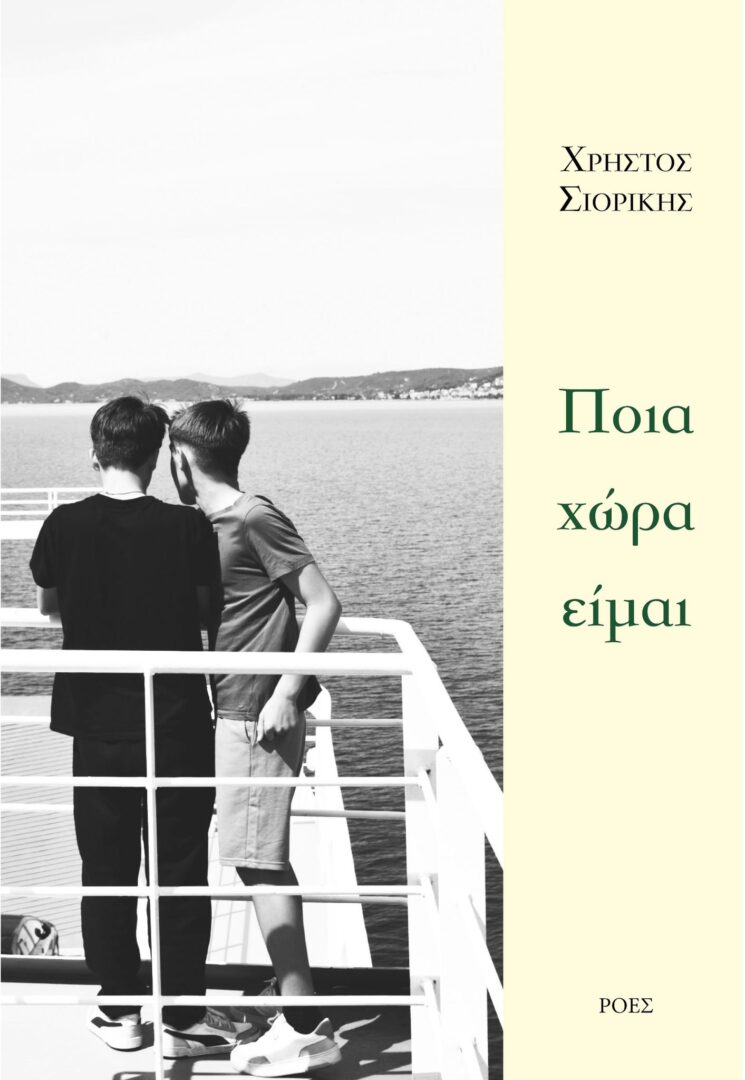

Your latest writing venture Ποια χώρα είμαι [What country am I] was recently published by Roes. Could you tell us a few things about the book and elaborate on its title?

I sometimes wonder if anything ever truly happens out of place; home, the foreign country of one’s travels, the land where we labor, the village of our ancestors, the distant and untouched terrain, the ancient landscape as revealed through science and history, the past of a familiar place, emerging through narration or photography, the war-torn zone seen only from the safe distance of peace, even our own body—all these are landscapes where life takes root and unfolds. All these spaces inhabit my latest collection, a body of work shaped over the years; meanwhile, everyday things happen, things that art seeks to illuminate, to question, to unearth so as to discover what lives beneath the surface.

When the phrase what country am I crossed my mind—seemingly on its own, not as part of a writing flow—I held onto it. I realized that it distilled both a personal search within my writing and a political wondering. Perhaps because a country has borders, that is boundaries. And boundaries are those that shape human life: they oppress, they define, they restrain, and at the same time, they ignite desire. Somewhere along the way, the phrase ceased to be just a question. It also became an affirmation: so, this is who I am—these are the doubts and convictions that define me, the forces that render me strong, and those that leave me exposed. This is how I see a border; this is how I long to pass from image to thing, from impression to event. I tried to speak of a secret—one that at times reveals itself, and at others disappears, leaving me alone. Between those two extremes, I take a position too; I make a kind of gesture toward the secret—toward that which resists control. It was, I think, in this spirit that I wrote the line: “I place the secret back where it belongs”.

Where does the inner landscape meet the surrounding environment in your poetry? In this respect, how multifaceted is the notion of “country” in your poems?

I believe the encounter between our inner – our emotional – landscape and the natural world or the surrounding environment begins somewhat “immaturely”.At first, we often try to project our most inner feelings onto whatever lies outside us, as a way of making it possible to write: the shape of a peaceful hill seems to tell me I’ve done something right, the scorched ravine says everything is wrong, the water in nature whispers that we long to live. But if we are to grow—both as human beings and as writers—we must seek a more honest exchange between our inner regions and the outer world. Through feelings and through language, I try to grasp how a city shapes my step, how it influences my choices; how a border makes me feel about freedom, about justice; how a tree or a breath of wind speaks to me—but not only about me.

In this book, then, the country attempts a kind of encounter, one that seeks to reveal something.

It is at once a geographical and political entity, and a region of the psyche. At times, it makes decisions, defines relationships; at others, it desires, it strives, it separates, it envies another. Perhaps I also wanted to play with the notion that no matter how structured or severe politics may appear, so many decisions and events rise from something deeply human and emotional—somewhere between map, historical fact, psychic event, and countless other layers, both the country and the person are searching for the stance they ought to take.

Let us attempt a condensation of all that has come before, woven through the verses of Mary Yosi: “And yet/ the heart is aflame/ lonely upon the map/ a hotbed of war” [from the poetry collection Η κοίτη, Smili (2021)].

The poems in this collection chart a passage through diverse terrains, conversing with both personal and collective histories. Where does the personal meet the collective in your work? Where do the various human micro-stories meet the History of the Earth and the world?

Our personal histories intertwine with the history of the world and of nature itself. Though the time scales may differ—human life appearing but a fleeting whisper against the vast epochs of history or the planet’s age—there lies within us a profound need to bridge these disparate times, so that we may not live in isolation. In my poems, I seek to place the speaking self within an archaeological inquiry, within another political system, another historical moment; to speak as a god, as a mountain.

Micro-stories are intimately common among all people. I perceive them as small events within the collective fabric, even when they bear something profoundly selfish or closed-off. Both the actions and inactions of the individual inscribe themselves upon the body of the earth—in the composition of the oceans, in the quality of urban life, in how we love, in the ways we seek and offer ourselves to one another.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

Language is both the substance and the tool of the art we create. Whether we employ it in everyday speech or explore its music, its history, and its infinite variety, we live within it. And in writing a poem, we unceasingly search for the right word, “the queen word of the world, [From the poetry collection Νηπενθή (1921)]” as Karyotakis so aptly put it.

Yet, before pencil meets paper, there is the ear. I am drawn to the music of a spoken phrase, and I find it fascinating how a spontaneously and swiftly uttered sentence can carry elements of astonishing density of meaning. I listen to people on the streets, in public transit, and of course, the flowing speech of children. Within all these moments lie diamonds that, even if they never become poems bound in books, they hold the power to open our ears—both to art and to other human beings.

Today, language endures a relentless assault; we often confront artificial voices of telephone customer service, AI-generated voices in videos we stumble upon on the internet, and poorly translated texts churned out by software. All these undermine the subtle nuances of thought and feeling, presenting language and words as something mechanical, predictable, and effortless. That is why, when a phrase spoken by a real human “escapes” their control—often revealing more than they intended—and when that phrase “shines” to the ears of those of us who persist in listening, it proves that the unpredictable, free part of humanity remains alive. And it is with this fragment that the product of this art, the poem, seeks dialogue: to arrive, whether in its slowness or intensity, against the imposed rhythm of calculated speech, and to propose anew a listening to language, a renewed hearing of the human need to exist and coexist.

Most scholars reckon that the content of a book cannot be separated from the particularities of the language that gave it shape. In this framework, where does the role and responsibility of the translator lie? Can translation ever be unethical?

The translator is called to face precisely this challenge: the uniqueness of a work’s language, and the delicate task of transforming and transferring that uniqueness into another linguistic framework. It requires patience, persistence, knowledge, and an ongoing investigation of both the source language and the language the work is translated into. It demands an attuned ear for something useful that may fall unexpectedly into our awareness, casting sudden light on a translational impasse.

Translation, in the end, is a form of invention: what will be the new, singular linguistic moment that can evoke an emotion corresponding to the original? (I often wish I could have spoken with Gatsos about how he worked with Lorca’s poetry). This is the ongoing struggle of the translator—who must sometimes betray the precision of a word in order to remain faithful to the feeling. As for whether translation can ever be unethical, I believe it can, if it is done thoughtlessly—when the translator seeks to impose their own vision upon the original, when they continually sacrifice the beauty of the source text to make things easier in their own language, when their desire is more to take than to give. A good translator always labors.

How do contemporary Greek writers converse with global literary trends? How does the local/ national converse with the universal?

I believe that those who write poetry and prose in Greek maintain steady relationships with other languages and literatures. Many often translate into Greek, and they draw significant inspiration from foreign writers—not merely because Greek is a “small” language, but because such connections arise as a natural necessity within art. In conversations with readers, one discovers works and voices from other countries, expanding one’s sense of what is being written across the world. You begin to trace elective affinities that span time and cut across distant geographies.

(Lately, I’ve been following with great interest The Parasite, a literary translation journal, and what it brings into our language.)

In our time, I don’t believe we can speak of clear literary trends or movements in the way we could a century ago. As someone who writes poetry, I try to seek out paths that connect writers and reveal common ground for sensitivity. Somewhere in that process, the local meets the global: in how the seemingly distant becomes deeply relevant, in how a poem written in a landscape so different from the Mediterranean can nevertheless reveal something intimate, something innately yours. And such connections rarely happen through intention or predetermined themes. The local becomes universal when it has delved, with sincerity, into the particular—into the specific.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE