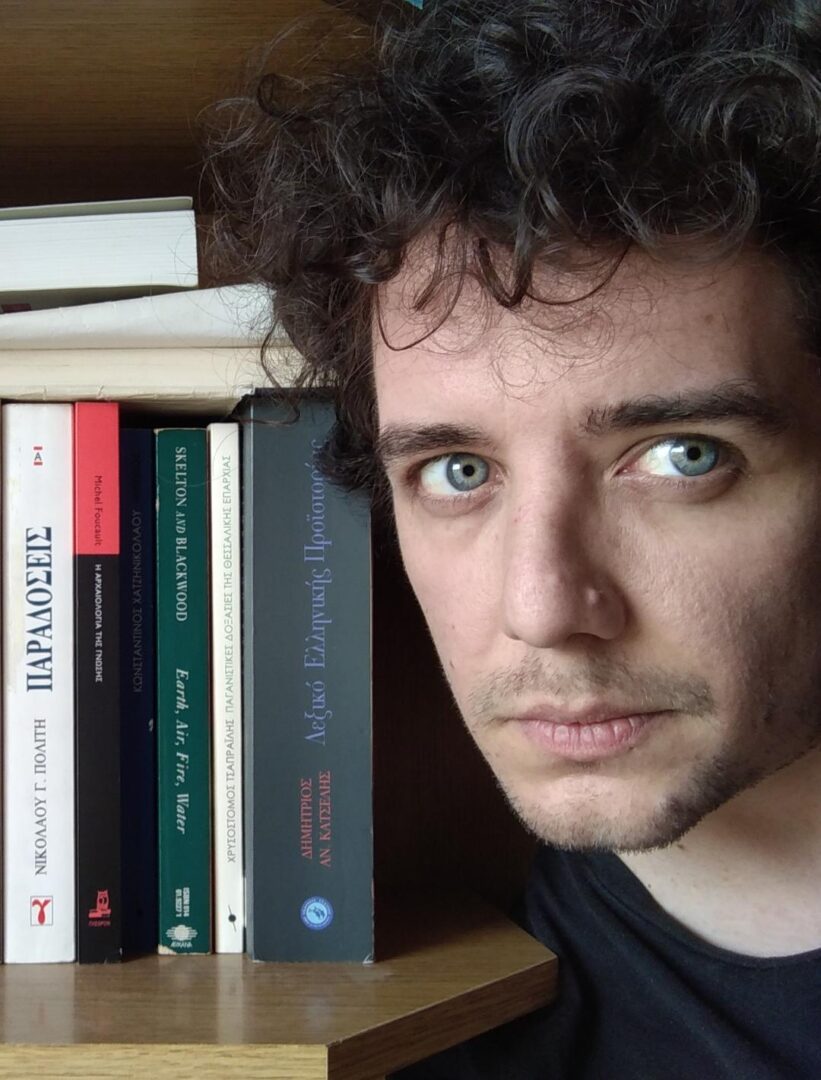

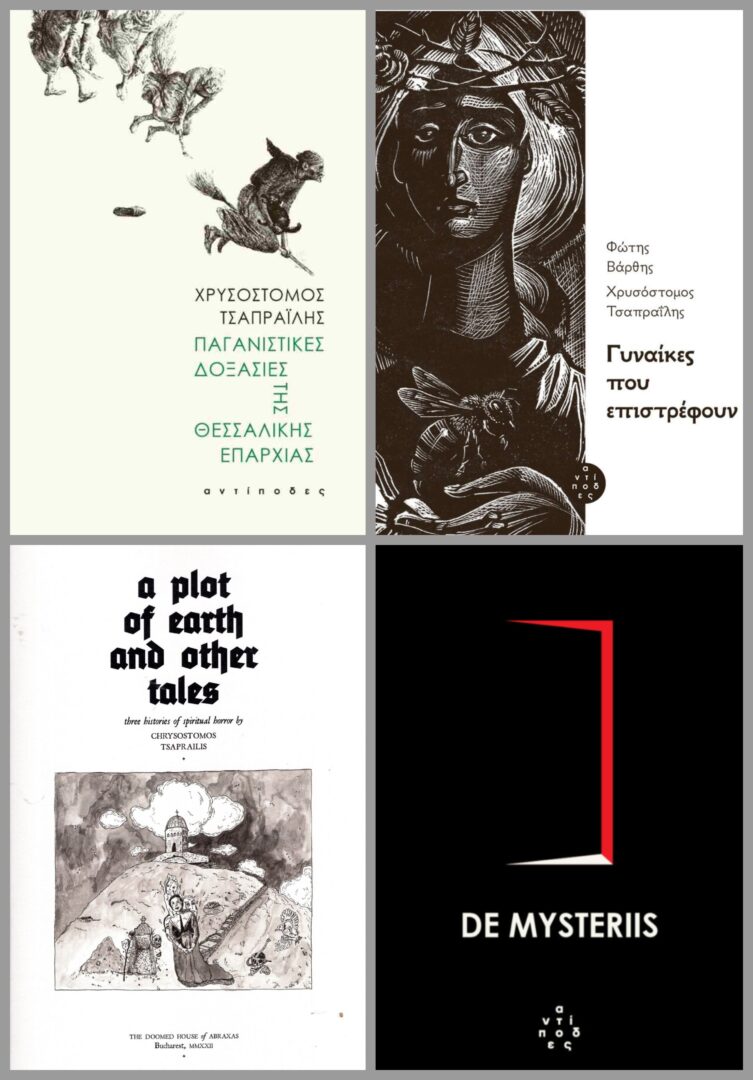

Chrysostomos Tsaprailis was born in 1984 in Larisa and grew up in Karditsa. For the past four years, he has lived in the Netherlands. He works as a fiction writer, translator, and video game writer. His published books include Pagan Rites of Rural Thessaly (antipodes, 2017), Women That Return (antipodes, 2020), A Plot of Earth and Other Tales (Mount Abraxas, 2022), De Mysteriis (antipodes, 2024), and Drawing Down the Moon (Ikaros, 2025). He has translated works by classic horror writers—such as Shirley Jackson, Arthur Machen, Thomas Ligotti, and M.R. James—into Greek. Some of his writings have also been adapted for the theater.

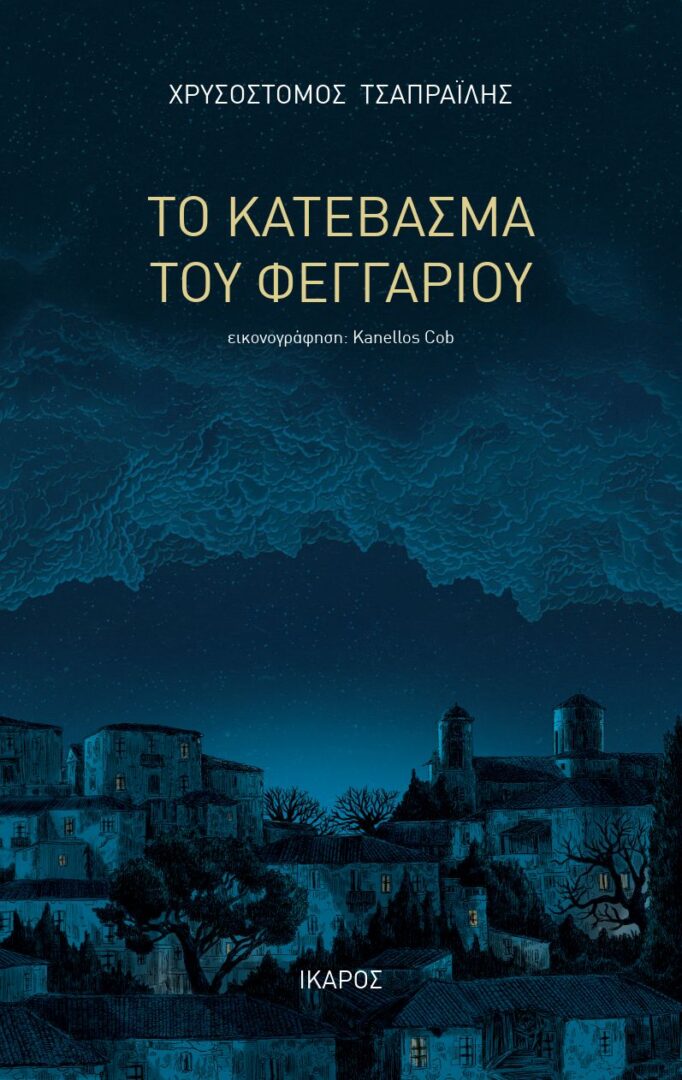

Υοur latest writing venture Drawing down the moon was published by Ikaros in 2025. Tell us a few things about the book.

Drawing down the moon is a folk-horror and mystery novella set in contemporary Thessaly, targeted toward young adult (14+) and adult audiences. The title alludes to the namesake rite (possibly the most famous coming from that particular area of Greece), which has survived since antiquity and has seeped into contemporary occult practice and pop culture. The book touches upon themes of immigration, female emancipation, conservatism, as well as the abandonment of rural settlements, all filtered through the lens of mythology, ancient tragedy, folklore, but also modern technology.

Plot-wise, we follow Kírkē, a freshman university student who visits her mother’s mountainous village for the first time in several years, in order to spend some time in her grandparents’ house before it is sold. There she finds herself caught in a web of strange phenomena and nightmarish situations, as the aspects of the village, the surrounding nature and its people become distorted due to the aforementioned ritual. In order to escape, Kírkē must seek answers in the village’s legendary past, solve two recent disappearances, and unravel the mystery of the disappeared local moon.

In your books, the traditions and legends of Thessaly are revived in the present in often peculiar and unexpected ways. How does this intertwining between the past and the present is achieved in your literary work?

Indeed, the revival of the legendary past in contemporary settings is a theme permeating my work, the ulterior goal being a sort of re-enchantment of our world. This is done by focusing on remnants of past legends and rites (be them authentic or re-imagined/invented) that evoke awe and wonder (two emotional states that are scarce in the modern world), images from my childhood, and uncanny elements of our own reality; then sieving and transforming everything through the sensibilities of my generation, and trying to organically reintegrate them in the now, ignoring the rules of cold-minded rationality. In the end, what I strive for is creating mythical versions of the world, versions which can act as sanctuaries for modern audiences disillusioned by both modernity and conservative/reactionary nostalgia.

“Μy aim is to re-enchant reality through an animistic perspective”. How does literature converse with its surrounding reality? Can it be used to defamiliarize the everyday and undermine the ordinary?

Not being bound by the physical and mental constraints of each particular era and worldview, literature can indeed initiate a dialogue with the surrounding reality, by giving voice to things that lack it nowadays. It can defamiliarize the everyday (and as a result repopulate it with wonder and awe) by looking at it from unusual angles (hence the aforementioned animistic perspective, which is quite alien to the modern worldview), by undermining dominant ideas about agency (providing it to animals, plants, things and phenomena usually considered inanimate) and the self-proclaimed superiority of the human species (something crucial in our era of climate change and environmental collapse due to human activity). In this way fiction, and especially speculative fiction, can be an instrument of radical change. In a more pedestrian level, it can provide relief by undermining the ordinary through the shattering of the dreaded routine, by populating familiar environments with unexpected twists and turns.

Your books fall into the speculative fiction genre. Tell us a few things about this genre and whether there is an increasing trend of speculative fiction in Greece in the last years.

Speculative fiction has been my favourite fiction category since a really young age. Its charm, as far as I am concerned, is its indifference for the limits of the reality of each era, its disinterest for the everyday, and its striving for creating new worlds (or imbuing our own with new layers) that can act not only as sanctuaries, but also as experimental spaces from which change can transfer to our reality.

In Greece, after many decades of marginalization, speculative fiction seems to have moved to the spotlight in the past decade or so, embraced not only by a wider public, but also by critics and publishers. There are many reasons for this: an increase in literary quality, cross-pollination with other genres, the embrace of the genre by pop culture due to the internet boom of the last 20 years, among others.

What about language? What role does language play in your writings?

From a language point of view, I try to keep my prose accessible to the modern audience, by not weighing it down with extended use of dialect, something which I find quite tiring whenever I encounter it as a reader. On the other hand, I try to insert snippets of marginalized languages and dialects, especially in names, like a hidden homage.

Since place and the environment have such a dominant role in my writings, I am especially interested in the role of language as an animating agent and as a prism though which unusual properties and aspects of the terrain can be revealed. I also try to take advantage of the rhythmic and evocative properties of language, especially in climactic moments of grandeur.

How do contemporary Greek writers converse with global literary trends? Where does the local/ national meet the global and the universal?

The borders between local and global have turned somewhat hazy during the last decades. This is a universal phenomenon not limited to Greece. Greek writers have obviously conversed with and adapted to global trends. As far as my area of interest is concerned, since the beginning of the previous decade there has been a global rise of interest in the intersection of art and tradition, the reinterpretation of the latter, and in the ways we can converse with the past; this has filtered down to the national scene in the last 10 years or so. The intersection of the local with the global can be seen everywhere: even works concerned with Greek tradition are often interspersed (intentionally or not) with elements from the greater popular culture, elements which have been branded in the writers’ psyche.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE