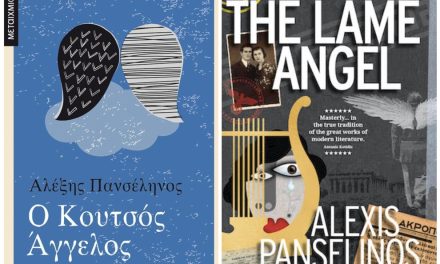

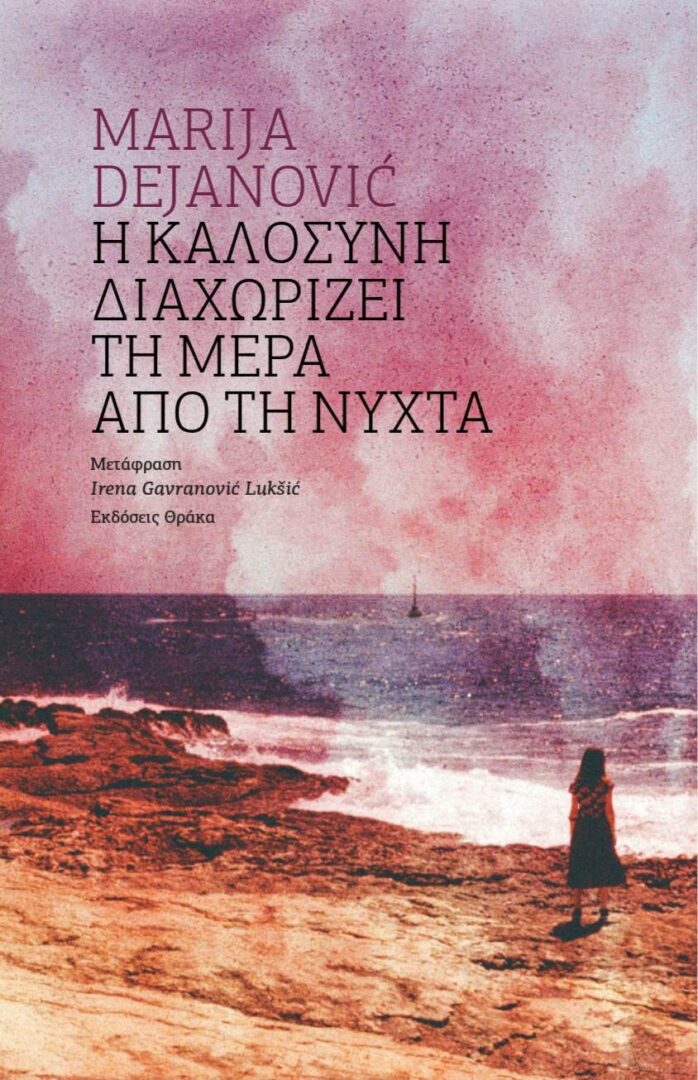

Marija Dejanović was born in Prijedor, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in 1992. She grew up in Croatia, Sisak, and currently lives between Zagreb, Croatia, and Larissa, Greece. She studied Comparative literature and Pedagogy (University of Zagreb). In 2018, her poetry book Ethics of Bread and Horses (Etika kruha i konja) won the Goran Award for young poets and the Kvirin Award for young poets. The poetry book Heartwood (Središnji god) won the Zdravko Pucak Award in 2019. Her third poetry book, Kindness Separates Night From Day (Dobrota razdvaja dan i noć) was published in Croatia (Sandorf, 2021), Serbia (Treći Trg, 2022), the USA (Sandorf Passage, 2023), North Macedonia (PNV Publikacii, 2023), Greece (Thraka, 2023), and shortlisted for the biggest Croatian award for poetry, Tin Ujević, and for the regional award Avdina Okarina (BiH).

She was awarded the Milo Bošković Award (2021), the Castello Di Duino (2022) Award, the DiBiase Poetry Contest Award (2021), and the Marin Držić Award (2020) by the Croatian Ministry of Culture for a dramatic text Ne moramo više govoriti, svi su otišli (We Don’t Have to Speak Anymore, They Are All Gone). Trilingual selections of her latest poetry were published in Greece (Kyklos Poiiton, 2020) and in Germany (Hausacher LeseLenz, 2022), and translated poems by the author were published in around 20 languages. She presented her poetry at numerous international festivals and readings. She is a member of the Croatian Writers’ Society, Croatian PEN Centre, and international poets’ and festivals’ platform Versopolis. She’s one of the editors of Tema and Libartes magazines. She is the assistant director of the Thessalian Poetry Festival and works as the editor of translated poetry for the publishing house Thraka.

Your latest poetry collection Kindness Separates Night from Day was recently published by Thraka. Tell us a few things about the book.

I was writing this book in the process of moving from Croatia to Greece. It is, in a way, a book about the departures and the arrivals, metaphorically and physically. It is also about the coexistence of the desire to love and the desire to be self-sufficient. Some critics called it migrant poetry, as it also thematizes my refuge from Bosnia to Croatia when I was a child. Others emphasized the presence of nature and animals and called it ecofeminist. All these different interpretations made me happy, as I like it when a book speaks to different people in different ways.

This is the 5th edition of Kindness, as it was already published in Croatia, Serbia, the USA, and North Macedonia. This makes me very grateful, as it enables the message I wanted to send with this book to reach more people. The message is: kindness is a force that gives life to the world. Kindness, often mistaken for weakness, is actually a source of bravery, activism, and emancipation, of everything in us that makes us want to act in ways that improve the societies we live in. In a world of exploitation, different types of inequality, and a cut-throat capitalist race, of isolated subjects, empathy is the core of both solidarity and self-love. I think we, as societies, lack both.

This is the reason I decided to write a primarily personal book. I wanted to focus on the problems of today, but also on the beauty that is still left in the world. As a great Croatian poet, Branko Čegec, once said to me – “today, only beauty can be truly shocking”. Everything else we have become desensitized to. In response to that, I said – “and in this world, only kindness can be truly radical”. In a world of aggression, empathy is the only thing that still has the potential to radically change things. I wanted to make the readers aware that they are a part of beauty and kindness that survives against all odds, and, in that sense, that they are strong enough to act on their behalf and on behalf of others.

I am very happy that Thraka published this book, so my Greek friends will finally be able to read it in their language. It was translated by Irena Gavranović Lukšić and edited by Katerina Iliopoulou, whose The Book of the Soil I adore, so the translation has to be great.

Υοu have published three poetry collections so far. Which are the themes your poetry touches upon? Are there recurrent points of reference in your writings?

My first two books were conceptual. It is hard to talk about them, as they seem to me as if they belonged to a previous life. It’s like that when you write concepts – they belong to your former self, and to the future readers. So, I will use some quotes that, I think, embody well what these books are.

Literature theorist Andrija Koštal wrote a paper on these books, claiming that while the book Ethics of Bread and Horses “questions the rigid borders between a human and an animal” and “questions the founding myths of our society”, the second book, Heartwood, “thinks a different type of community, rooted in love and compassion” that “simultaneously speaks about the history of one micro-community, and the Earth”, thus “insisting on phenomena not existing only as a part of the human life, but being a part of the long-term time” in a “natural environment as a place of mutual dependency”.

Poet and critic Davor Ivankovac wrote that “Ethics of Bread and Horses stands inside the Croatian poetry field as a convincing sign of Difference, whether we read it as an allegory of human experience, as a critique of the patriarchal narrative of female Otherness […], as […] a poetic myth about the origin, or as an example of pure aesthetical larpurlartism”, naming it “an extraordinary project with a focus on a concept that is rarely seen”.

So, I think conceptualism, indirect activism, focus on female identity, relationships of subject and the space, and presence of the natural world could be recurrent points of reference in my writing, as they are present in Kindness […] too.

You are part of the editorial team of ‘Thraka’ literary magazines and editions, which have contributed to new poetic voices being heard and published. Tell us a few things about your experience.

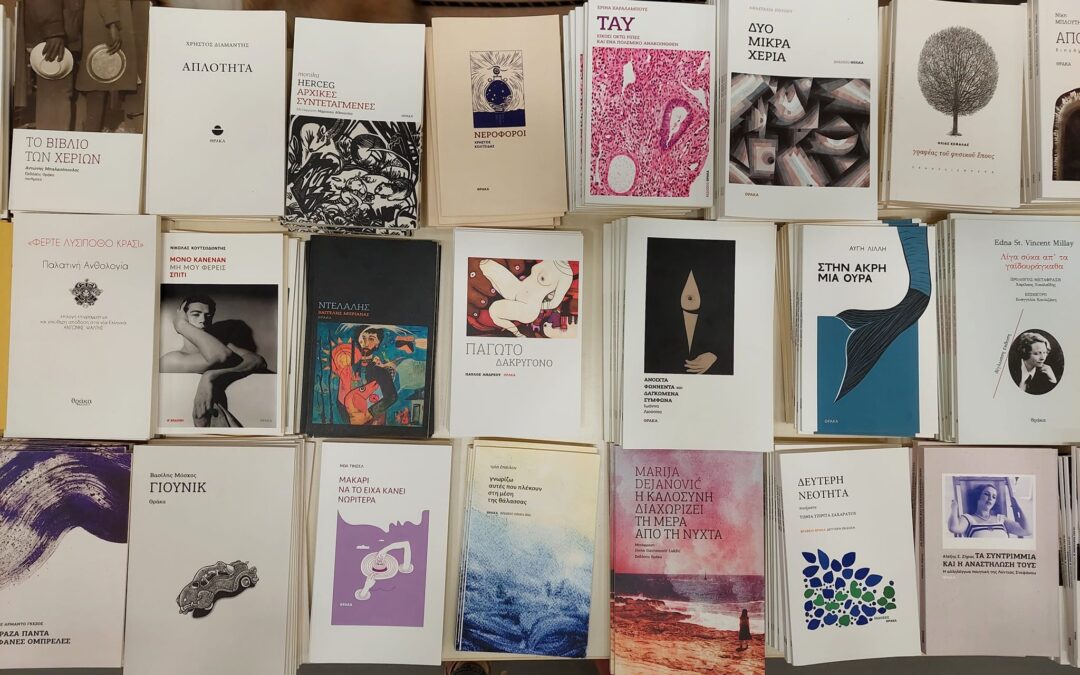

I feel very blessed to have the opportunity to be a part of something like Thraka. What Thanos Gogos does is not merely publish books. It is living a life dedicated to creating a place that values poetry, that nurtures it, that makes it important, as it is and should be important. It is amazing to watch Thraka and Thessalian Poetry Festival grow like a big plant that was planted with love and watered with hard work. I learned a lot from this experience, and I am still learning. Not only about how publishing functions and how the festival is organized, but I also discovered many amazing Greek poets.

What I like about Thraka the most is that here it doesn’t matter what’s your name, what your biography looks like, whether your work will sell or not, or who likes you or dislikes you. The only thing that matters is: Does this book have anything to offer? A great writing style, a unique author’s voice, an interesting perspective on the world, or a relevant topic. If this book needs to be read by at least one person, we publish it. This year, we published four books that I am very proud of: Noa Tinsel’s [Vagia Kalfa’s] Μακάρι να το είχα κάνει νωρίτερα (I wish I had done it earlier), Το βιβλίο των χεριών (The book of hands) by Antonis Balasopoulos, Γιούνικ (Unique) by Vasilis Moschos, and a Greek queer poetry anthology, in collaboration with Rosa Luxemburg Greece. We are also preparing a poetry book by an excellent Portuguese scholar and poet Tatiana Faia, translated by Tonia Tzirita Zacharatou.

For the majority of young writers, writing is not a main profession but rather a leisure time activity. In other words, earning a living through writing is the exception rather than the rule. Which are the main challenges new writers face nowadays in order to have their work published?

Today, leisure time is so commercialized and commodified that the circulation of capital is present in almost every activity people engage in in their free time. On the other hand, intellectual work and art work are disregarded and not considered “real” work. Why is writing non-commercial books today not considered “real” work?

The root of this problem can be found in the traditional romanticist cult of a poet-genius, which is still prevalent today. It is an image of an author who, first of all, writes almost unconsciously, under a strong burst of inspiration (romantic poets, though, also took the editing of poetry after the initial burst of inspiration into account, but they still emphasized inspiration as primary). Secondly, the romantic genius is supposed to write out of pure, idealistic love for creation.

We must not lose sight of the fact that such an idea of the author has its own historical and socioeconomic context, which is that at the time of its prevalence, most authors of poetry were privileged men. Although many of them supported the French Revolution, the concept of nobility, which they attributed to poets – themselves – still contained aristocratic ideals that remained in their mentality. They did not perceive literature as work because, first of all, if it was work, it meant that they were not special – aristocrats of the spirit – but just mere craftsmen who used words as their material. This wasn’t how they wanted to think about themselves, they felt they were above it. Secondly, they did not have to sell their works because they were members of higher social strata, so they could afford to move their notion of the writing process into the sphere of the ideal. These people were the social elite, but also the cultural elite that left us with this notion of writing as noble activity of special individuals. I would rather just be perceived as a regular person whose tools are words, as it is closer to the reality of poets today.

Today, the conditions in which literature is created have changed a lot – writing has become more democratized on the one hand, and on the other hand, we have accepted that writing and editing are work. But we still don’t see it as labor. Although the conditions of writing poetry have changed, this romantic image of the author remained present in the collective unconscious, and its consequences remained in the realm of the visible: poets paying thousands of Euros to be published, newspapers that sell millions of copies publishing poetry without any author’s fee. The basic problem of the poets’ literary work is, in short, that we are not able to stand in solidarity and find a way to unionize.

It is a paradox that puts poetry in an awkward position – the publishing became more and more commercialized – dependent on the market, as the funding for literature in Greece is not adequate, and the authors – the production workers in this sense – have no way to even start to conceptualize the basis of their workers’ rights.

In the last few years there has been an extraordinary burgeoning of poetry in every form: graffiti, blogs, literary magazines, readings in public squares. How is this strong civic presence to be explained? Could poetry offer new ways to imagine what can be radically different realities?

Poetry is a form of writing that can create a radically different reality. It contains both concentration, complexity, and thickness, as well as blank spaces, emptiness, the missing parts. That is why you can never read the same poem twice. It is always a new creation, a new knot of meanings. In that way, with an active reader, poetry is both timeless and an anticipator of the new time. It already has a possible future written in it, it is just waiting for the reader to unlock it. Our possibility to create and understand metaphors is what makes us also capable of creating and understanding a possibility of a different world existing.

In general, I believe that the possibility to understand a metaphor is what makes humans human – different from other animals, and different from artificial intelligence. This capability of operating neither on the obvious, primal, immediate (like animals) nor on the dichotomy, binarity, linearity, one-track-mindedness (like AI), is what makes it possible for us to dialectically create a new reality that is bigger than the mere collection of elements from the previous one. That is why I like to believe that all art is inherently political – not only because of the politics that affected its creation, but because of the future politics that are implied in the text – whether in its structure, or its meaning – and co-created by future readings.

How do young writers relate to world literature? Where does the local and the national meet the global and the universal?

“World literature” and “universal” are consensuses that not many people had agreed upon, but we all accept them by inertion. I had the privilege to travel to many festivals, book fairs, etc all around Europe, and I saw that there are no “small literatures”, only small budgets for culture. At every festival, there is a local poet you’ve never heard of that knocks you out of your boots with the verses they wrote in their small village in a country you previously knew nothing about. The most beautiful things often come in silence – without the fanfares of marketing, without the flags of the Western centers of cultural production.

The world canon is shaped by geopolitics and market logic. That is why it often bores me. Certain types of writing, legitimated by aesthetics that are backed up by the cultural policies of rich countries, hold a monopoly that is so strong that it has almost nothing new to offer anymore. This type of writing constantly reproduces itself and broadcasts its products so intensely that it all starts to look the same. I think that this is why we can see more inclusivity as a trend in publishing now – not because the big markets became interested in us, but because they, too, got bored of themselves. I’m interested in writing that doesn’t chase global trends – in peripheral, experimental, idiosyncratic, decentralized, overlooked. I want to find out about those books without selecting them and observing them through the lens of the cultural centers of the West, which often reduce them to wars, poverty, or whatever issue is in trend at book fairs that year.

We in the Balkans are one of these peripheries, and that is why I feel free. My creation is not burdened by the desire for success, as I think that there is no such thing as a “successful author” here. You can be the most known Balkan author in the world, or the one with the most acclaimed works, but still, on the larger scale of things, I don’t think many people in the world would care about your existence for a longer period of time. In that sense, I don’t care if I relate to world literature in any way. I care about the world of literature. The community, the beauty, the knowledge, the power to speak and the privilege to listen. This is where I find joy.

*Interview by Athina Rossoglou

INTRO IMAGE: © Maša Seničić

TAGS: LITERATURE & BOOKS | READING GREECE